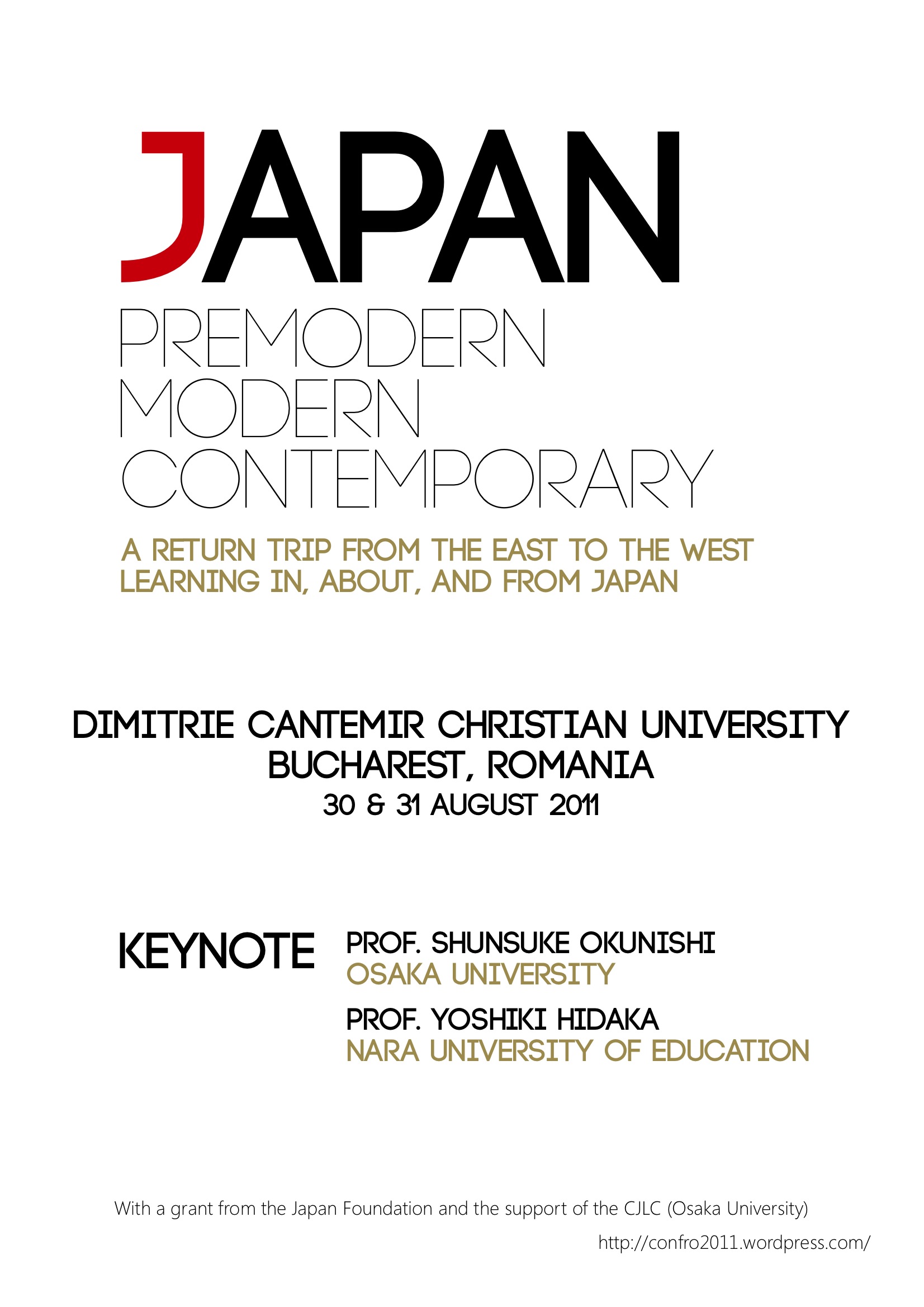

Below are the abstracts of the papers presented at the first edition of the conference. We had parallel sessions about culture, literature and linguistics, and over 30 participants from 10 countries.

Keynote Address: Okunishi Shunsuke, Osaka University, Center for Japanese Language and Culture

The Serpent Myth in Japanese Culture

It is my belief that, within the field of cultural studies, any theme must be analyzed in a global context. Particularly in the case of cultures such as Japan, where the object of study are not only old records, but also traditions and rituals that have been kept alive since old times until the present, both past and present manifestations must be taken into account. My presentation will focus on one such aspect, the Japanese serpent beliefs, which were recorded in the 7th century chronicles “Kojiki” and “Nihonshoki”. One legend focuses on the myth of a serpent—embodiment of the visiting deity—who comes to meet a maiden every night. The other is the story of the princess initially offered as a sacrifice to the serpent god, who will be later rescued through the slaying of the serpent.

Both stories are based on a universal prototype: the serpent is the primordial god, and to slay the serpent and marry its sacrificial victim (daughter or wife, in other versions) is a symbolic way of renewing the universe. Representations of this myth can still be observed in modern-day kagura performances.

Ritual and Tradition

Carmen Tamas, Osaka Electro-Communication University

Salt, Fire and Water: Means of Entering the Sacred

Pollution and purification are two concepts often used in relation to traditional Japanese culture and its peculiar rituals. From the elegant wells placed near the entrance to shrines, inviting visitors and believers alike to perform the customary ablutions (sometimes clear instructions are displayed in plain view), to the mounds of salt placed near house gates or restaurant doors, to fierce-looking yamabushi who walk on fire, once we immerse ourselves into the Japanese culture, we are surrounded by symbols that seem to indicate a desire to separate the sacred from the profane and to purify oneself in order to prevent disease, misfortune, or the wrath of gods.

However, “purification” is a widely misapprehended concept, particularly in the case of Japanese rituals, and salt, fire and water are used not necessarily to cleanse, but to perform magic acts as well. In an attempt to shed some light on this matter, I shall discuss the significance and the role played by the above-mentioned elements in Japanese tradition, focusing on five specific examples.

The magical function of salt becomes apparent is the Hari-kuyō ceremony from Awashima Jinja in Wakayama. Hari-kuyō (“religious service for needles”) is a ritual conducted annually on February 8th, when rusty or blunt needles from all over the country are collected at the shrine in order to receive a symbolic burial under a big rock, being first covered in salt.

The symbolism of fire will be discussed in relationship with three major events: the Yassai-Hossai festival, which takes place at Ishitsuta Jinja in Sakai (Osaka), on December 14th, the Saitō Ōgomaku rite performed at Gangoji Temple in Nara on Setsubun Day, and the torch dance performed by “demons” at Nagata Jinja, in Kobe, also on Setsubun Day. On all three occasions, fire appears as an extremely potent element, able to both bring something of the sacred into this world and to open the gates to the other. Fire establishes a connection between the known world, inhabited by living humans, and the world of spirits and things passed.

Water, on the other hand, is the element which prepares the participant in the ritual for this passage into the sacred, what is often seen as a “purification” practice being in fact a gesture related to asceticism and shamanistic techniques. In this presentation I shall introduce the “purification” rites performed by the men who play the demon roles during the tsuina-shiki ceremony from Nagata Jinja, known as suigyō (literally, “water practice”), a term identical with the one used by priests from the Nichiren Sect to indicate the harshest trial of their ascetic term: the daily ablutions. It is my intention here to focus on fire and water not as instruments in symbolical (and superficial) rituals whose original meaning and intent have been long forgotten, but as powerful elements, which still inflict a considerable amount of pain on the practitioners and thus facilitate if not their entrance to, at least their communication with a different world.

Raluca Nicolae, Spiru Haret University

In Search for Chimeras: Hybrids of Japanese Imagination

In Greek mythology, the Chimera was a monstrous fire-breathing female creature, composed of the parts of multiple animals: the body of a lioness, a tail that ended in a snake’s head, a head of a goat rising on her back at the center of her spine. In Theogony, Hesiod describes Chimera as: “a creature fearful, great, swift-footed and strong, who had three heads, one of a grim-eyed lion; in her hinderpart, a dragon; and in her middle, a goat, breathing forth a fearful blast of blazing fire”. The Chimera was the daughter of Typhon and Echidna. In another version the Chimera mated with her brother Orthrus and mothered the Sphinx and the Nemean lion. When she ravaged the Lycian country, Iobates sent Bellerohon against her. He slew the monster from the back of Pegasus. The name has come to be applied to any fantastic or horrible creation of the imagination, and also to a grafted hybrid plant of mixed characteristics. Apart from the Greek mythology, the Oriental imagery has created its own pictures of Chimeras. Winged Chimeras form one of the most important groups within the domain of the tomb sculpture and hold a key position in early Chinese animal sculpture (Barry Till). In addition, the Japanese folklore has also produced examples of such an imaginative hybridization: Nue, Baku, Rai, etc. Nue is a legendary creature with the head of a monkey, the body of a raccoon dog, the legs of a tiger, and a snake as a tail who can sometimes turn into a black cloud. The most famous story involving Nue is told in The Tale of Heike: in 1153, the Emperor Konoe began to have nightmares and to fall ill. The source of illness was a dark cloud that appeared on the palace roof every night. One night, the samurai Yorimasu Minamoto stood watch when the cloud appeared and shot an arrow into it, killing Nue.

Baku is a spirit who devours dreams and is sometimes depicted as a supernatural being with an elephant’s trunk, rhinoceros eyes, an ox tail, and tiger paws. In China it was believed that sleeping on a Baku pelt could protect a person from pestilence and its image was a powerful talisman against the evil. In Japan, the kanji for its name (獏) used to be painted on pillows as a protection for sleepers (Brenda Rosen). Rai (lit. “the thunder animal”) was a legendary creature whose body is composed of either lightning or fire and may be in the shape of a cat, tanuki, monkey, or weasel. In the manga and anime versions of “Fullmetal Alchemist” as the result of a specific alchemic transmutation. Though some of them are a fusion of two animals, there are some that were humans infused with animals which play a role in the series’ storyline.

The above evidence indicates that monsters are not mere metaphors of beastliness: their veneration as well as repugnance form the displaying the image of a stark dualism (the numinous feature).

Chomnard Setisarn, Chulalongkorn University

Meanings and Symbolism of Blood Sports

Today blood sports or combat sports are often considered as a type of entertainment or form of play – a way of amusing oneself and others. But from a cultural perspective, most of them have not arisen solely as forms of entertainment.

Japanese traditional sports such as sumo, tug of war and ishigassen (stone fight) also hold significance as fertility rites, rites that can be themselves categorized into many types –consider these examples: Toshiura – an augury for predicting what will happen in a year; yoshuku-girei, a ritual celebrating in advance of the coming abundant harvest; suii-girei, a ritual praying for fertility and held at every stage of the crop’s growth.

Blood sports and combat sports are also important as a site of the performance of hounou-shinji, Shinto rituals dedicated to kami (Japanese gods). It can be said that amagoi sumo (Sumo rites praying for rain) are performed in order to evade disasters such as drought. Konaki sumo (crying children’s fight), a rite that uses the power of the child’s cries, is said to be able to save children from any illness, showing that these rituals also have meaning as a method of harnessing supernatural powers.

Blood sports and combat sports are symbolic of a form of conflict. According to the principles of fighting, it is accepted that participants will be divided into two groups and they then compete to decide a winner. However, the contents or conditions of the conflict (e.g. rice vs. crops, man vs. woman, adult vs. child, kami vs. human etc.) differ greatly depending upon the region, because the different circumstances, beliefs, cultures and traditions of each area will be reflected in the style of conflict.

Modern Literature

Luciana Cardi, L’Orientale University of Naples

Challenging the Traditional Notion of Japanese Novel: Grecian Myths in Yumiko Kurahashi’s Fiction

This paper explores the rewriting of Grecian myths in contemporary Japanese literature, focusing on Yumiko Kurahashi’s fiction. Kurahashi’s literary works, such as Amanonkoku Ōkanki (Record of a Voyage to the Country of Amanon) and Hanhigeki (Anti-tragedies), challenge the traditional concept of the novel by mixing together different literary genres, and by reworking the themes of Grecian myths.

For instance, in Amanonkoku Ōkanki, the myth of the Amazons is twisted into a new story, pointing out the issue of the construction (and fictional nature) of female identity and parodying the contradictions of Japanese society. The narration focuses on the linguistic and cultural gaps between a patriarchal missionary, called P, and the members of the country of Amanon, where women dress and act like men. In the interaction of P and the inhabitants of Amanon or, in other words, in the encounter between the Grecian hero and the Amazons, the difference between male and female points of view is increased by a strong gap in their respective linguistic and cultural codes, which gives rise to several misunderstandings. Along with the narration, Amanon becomes a deforming mirror distorting the social order and the cultural background of P’s patriarchal country, and it gradually comes to resemble contemporary Japan, with its striking difference between appearances (tatemae) and reality (honne). Thus Grecian myth is reworked to undermine the concept of male and female identity, conveying a disturbing image of Japanese society.

Similarly, in Hanhigeki, Kurahashi sets the stories of Oedipus, Orestes and Medea in Japan. She rewrites the Grecian myths and the tragedies by Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides within a narrative structure that reveals the process of reality construction, interfering with the mechanisms that build up the characters into a unitary selfhood. For example, in the story “Kakou ni shisu” (Die at the Estuary), Oedipus is an aged employee at Tokyo university, Mr. Takayanagi, who decides to return to his hometown and spend the last years of his life in a house near the estuary of a river. Like the protagonist of Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus in Colono, he is followed by his young daughter, Reiko, who ignores the past events haunting him. In this context, the myth becomes a disturbing element that affects the space and time dimensions inside the story, creating a multi-layered, surreal narration. As the narrative structure continuously shifts from the third-person objective narration to the dreamlike world of the mythical subtext, and from past to present in Takayanagi’s stream of consciousness, the distinction between reality and fiction is blurred. Consequently, the events evocated by the protagonist’s memories cannot take the shape of a univocal, objective narration, and the readers are alienated from the reality being represented.

Monica Tamas, Osaka University

The Female Body in the Works of Enchi Fumiko

My presentation explores the role of the female body in Enchi Fumiko’s literature. Particularly, it focuses on a limited number of works such as Kuroikami (Black god, 1956), Yō (Enchantress, 1956), Mimiyōraku (Earrings, 1957), Onnamen (Masks, 1958), Fūfu (The married couple, 1962) and Hanakui uba(The flower eating crone, 1974) and aims to illustrate the relationship between the depiction of the female body and the female character’s psyche and becoming.

One of the prominent female writers of the postwar period, Enchi Fumiko (1905-1986) succeeded in describing the modern “real woman” in her works as she delved into the dynamics of gender in modern society. By doing so, she criticized the persistence of values belonging to the patriarchal system that preserve the idea of gender difference to the detriment of women.

Enchi challenged the idea of a purportedly standard universal body that is an idealized composite of the “best” features of real bodies and to which women are being subjected to. As some feminists have argued, for women, the body is a primary signifier of the self to the outside world and the links between identity and embodiment are more explicit for women than for men. This should be taken as one of the main reasons why Enchi felt the need to explore the characters psyche by relating it to the female body. Furthermore, there is a close relationship between Enchi’s biography and her fiction, regarding issues of sickness and corporeal suffering.

In Enchi’s fiction the decaying female body is portrayed as one no longer fit to live inside the system because it doesn’t fulfill the parameters of the sexualized ideal female body within the social mentality. Subsequently, the female characters are placed outside the social system or at its periphery. Moreover, it appears that old age by itself is a peripheral territory.

In Enchi’s works, living with a radically unpredictable body or a body that has lost functions or parts calls into question the stability and continuity of identity. The changes in the body are interpreted as a crisis or as aberrations or deviations from the norm rather than natural variations within a field. Enchi demolishes the myth of the perfect female body and breaks taboos by raising issues related to it that have not been accepted previously within the literary tradition. She represents women’s corporeality by taking up elements that are being purported as being characteristic of the female body or of the devaluation of it. Among these, she discusses elements such as menstrual blood, the loss of sex organs, childbirth, abortion and the devaluation of the female body because of age.

Enchi discusses the abjection of the maternal body in works such as Onnamenand Kuroi kami, the repressed female sexuality in works such as Mimi yōraku, Yō and Hanakui uba and the wretchedness of old age in Fūfu. She also analyzes the subjectification of women within the phallocentric system of the patriarchal Japanese society and in my presentation I analyze how the oppression of women by men is being projected on the female body. By confronting patriarchal values some of the characters come to affirm their identity and free themselves from the constraints of patriarchy.

Adelina Vasile, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

Inside Out: Symbolic Spaces in Haruki Murakami’s Fantastic Fiction

This essay explores descriptions of places/landscapes in Haruki Murakami’s major fiction. The settings in which Murakami’s characters appear abound in sterile, bleak and/or murky spaces (vacant plots of land, a Mongolian desert, a walled town called the End of the World, the sewers and the tunnels of the Tokyo underground, forests, dry wells that force characters to confront their inner demons). These spaces characterized by emptiness, depth or darkness are not mere landscapes. Examples suggest that the scenes described are almost external manifestations of the emotional lives of his characters, more or less direct projections of the interior states of the characters; there is a fundamental nexus between interiority and exteriority – landscape. These landscapes are places of retreat where characters (who often feel like empty shells and are haunted by a sense of loss) enclose themselves inwardly and try to make sense of the senseless. Even if they are empty, they are spaces in which something creative can occur – such as the capacity to encounter undiscovered aspects of the self. These projected versions of states of mind are full of potentialities, being favourable for revelations, epiphanies, experiences of the numinous. The majority of these landscapes function symbolically as realms of the subconscious, where the ultimate source of the self is rooted. It can be said that the subconscious is the natural habitat of Murakami’s characters.

Guest Speaker: Lucia Dolce, School Of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Ritual Interfaces: Tantric Buddhism in Mediaeval Japan

Scholarly analysis of Japanese Tantrism has uncovered only a tiny part of the variety and richness of the doctrinal systems and ritual practices created in Japan. This is somewhat paradoxical when one considers the paramount influence of Tantric modes of thought on Japanese Buddhism and Japanese culture in general, compared to other countries of the East Asian Buddhist sphere, as well as the influence that Japanese emic categories of analysis have exerted on the study of East Asian Tantras.

Taimitsu, the esoteric Buddhism of the Tendai lineages, is one of the two major traditions of Tantric Buddhism in Japan, the other being the Shingon school. Despite its historical importance, Taimitsu remains largely unknown to scholars, including those of Japanese Buddhism. The ritual dimension of Taimitsu has received even less attention. Some analysis has been carried out of the initiation rituals into the practices of the Womb and Diamond mandalas, which were part of the training of a Tantric specialist, and today are much the same in the two Tantric schools. Largely unexplored in their historical, doctrinal and performative development are the rituals devoted to individual figures of the Tantric pantheon (bessonhō). These have often been regarded as minor liturgies, because their purpose is the attainment of immediate worldly benefits, rather than the practitioner’s enlightenment, and in this sense they do not conform to the outcome prescribed by a philosophical approach to Tantric practice. Yet they constituted the greatest number of Tantric liturgies performed throughout the premodern period, and several were newly created in the mediaeval period.

This lecture analyses two such rituals, which became distinctive of Taimitsu lineages: the ritual of the Blazing Light Buddha (shijōkōhō) and the ritual of the Venerable Star King (sonjōōhō). The first ritual was the most important of the “major liturgies” (daihō) of the Sanmon lineages, which were performed by imperial order for the protection of the state and the wellbeing of the emperor. The ritual was brought to Japan by Ennin and was performed initially in a hall constructed on purpose on Mt Hiei. The second ritual was devised by monks of the competing Jimon lineage, as a counterpoise to the shijōkōhō. It took its name from a deity of Japanese creation, called Sonjōō, considered to be a personification of the Polar Star.

The lecture will discuss the dynamics of creation of these rituals, considering in particular their multilayered iconographies and spatial organization. It will then explore the role that these rituals played in the process of political legitimation of Buddhist lineages, as well as the sectarian agendas that affected their differentiation and performance.

Guest Speaker: Atsuko Nishikawa, Doshisha University

Spatial Transformations in Izumi Kyoka’s A Map of Shirogane

The first words that come to mind when one mentions Izumi Kyoka’s name, are, perhaps, “fantastic” or “other-worldly”. Nevertheless, not all of his works have as their background a fantastic world; in some, a real place becomes the stage of the events described in the story.

In this presentation, I will focus on A Map of Shirogane (published in Shin-shousetsu, January 1916); by looking closely at the role played in the economy of the novel by the image of actual places and architectural structures, I will attempt to shed some light on some of the particularities of Kyoka’s prose.

The main character in the novel, Hagiwara Yogoro, is an old kyogen actor, who has to play the role of Hakuzosu in Tsurigitsune. The story begins with him reminiscing about how he had once got lost in Tokyo, on the way to Shirogane; there, he had met Omachi, a student of the University of the Sacred Heart (Seishin Joshi Gakuin), who had taken out a map and helped him find his way. In order to play his role convincingly, he decides to go back to Shirogane and look for Omachi, the girl who had left such a deep impression on his heart. He finds Omachi, who, even though rebuked by her father, decides to consent to Yogoro’s plea, touched by his enthusiasm. This is how the story ends; Yogoro’s character is based on an actual person, and A Map of Shirogane has been so far analyzed mainly as an “artist’s novel”, with critics laying emphasis on Yogoro’s desire to perfect his skill as an actor. In my opinion, though, this interpretation takes into consideration only one aspect of Kyoka’s novel.

In my presentation I intend to focus on the way Shirogane is described, as seen through the eyes of the main character, Yogoro. Especially, the University of the Sacred Heart, which was built in the western architectural style in Shirogane, Tokyo, in 1910, can be said to play a central part in the novel. As sites for acquiring advanced western learning and culture, many colleges had been built, since the beginning of the Meiji period, in the western style, so in that sense there is nothing particularly new or remarkable about the structure of the University of the Sacred Heart. Rather, what is remarkable is the way in which the old man gradually comes to see it as two overlapping images: as a western architectural structure, and as an Inari (fox deity) torii, which had been a site of reverence since ancient times. His viewpoint might be seen to imply the gradually changing face of Shirogane, where the quiet residential site of a samurai family’s villa is transformed by the construction of a university. Through the detailed analysis of the images of the actual places and buildings described in the novel, I will attempt to clarify the way Kyoka articulated the consciousness of the people living in these changing spaces and went on to create a unique world of his own.

Ritual and Tradition

Fumi Ouchi, Miyagi Gakuin Women’s University

Liturgical Chanting in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: Mediating the Dead and the Living

The development of different types of ritual for the dead in the Japanese Buddhist tradition is an important theme to discuss in order to explore how Buddhism, which had originally nothing to do with rituals for the dead, took root in Japan. This is typically seen in the case of the practice designated nenbutsu 念仏 (Ch. nienfo). It was developed from its Chinese prototype in an original way in Japan, and was associated with different types of ritual for the dead. Even Genshin’s system, which reconstructed the nenbutsu tradition and reconciled it with Tendai contemplation practice for attaining enlightenment, maintained a deep concern for the dead. After Genshin, the nenbutsu movement developed in multiple directions: typically, the Pure Land masters advanced devotion to the Buddha Amida through the practice of simply calling his name, and unordained monks, hijiri, advocated faith in sacred places as entrances to the Pure Land. These movements brought about the development of various types of rituals and performing arts centring on the chanting the Buddha’s name, that were enacted for the purpose of easing the dead. The theme of death, and the pacifying, or healing, of the dead was deep-rooted in the Japanese religious tradition.

This paper will investigate how the nenbutsu tradition dealt with human death and the dead, and how the understanding of death and the relationship between the living and the dead changed, and what that change signifies. To do so, it will analyse, using a performative, ethnomusicological and socio-historical approach, first, the deathbed ritual devised by Genshin, second, the ceremony performed at Taimadera Temple in Nara representing Amida’s descent with his retinue to the death scene, and third, some other folkloric nenbutsu rituals. Genshin constructed the ritual as a vocal performance enacted by a dying person and his fellows attending the deathbed. The ceremony at Taimadera is co-performed by Shingon priests who play music of this world and Jōdo priests who chant hymns representing the Pure Land. A group of folkloric nenbutsu rituals transmitted in Yamanashi prefecture use male vocalisation for the purpose of purifying a newly deceased person, while female vocalization as an agency to pacify and ease those who had died earlier. Female mediums called itako or kamisama depict an impressive scene of reunion with a dead person, skillfully using vocal techniques. From these actual performances, and methods of vocalisation above all, we can see that the basic function of the chanting was to establish a close relationship between the dead and the living, and how the efficacy of different types of vocalisation worked as a strategy for doing so. The balanced flexibility of vocal performances involves the audience with the ritual and consequently with the dynamic process of continuously recreating the relationship. This offers an insight that Buddhist traditions in Japan are far more perfomative than is generally understood, and emphasises the critical role of the dead in powerfully supporting the living.

Shogo Kanayama, Gatsuzouji Temple

From Vengeful Spirits to Tragic Ghosts—Ghost Imagery in Japanese Culture

The belief that at death the soul separates from the body and becomes a spirit is universal; however, in Japan these spirits are divided into two categories: benevolent spirits called nigitama and malevolent spirits called aratama. The reverently worshipped nigitama dwell on the mountains as spirits of the ancestors and in spring they descend as gods of the fields to protect the crops. On the other hand, the aratama turn feelings such as bitterness, wrath and desire for revenge into a kind of malefic energy which brings misfortune. Nevertheless, it is the Japanese belief that neglecting to worship the ancestors’ spirits can have evil consequences, while paying the due respect to vengeful spirits can turn them into gods of good luck. Even nowadays, at Izumo Taisha, one of the biggest shrines in Japan where people go to pray for happy marriages, special services are held to appease the spirit of Ōkuninushi, who, according to Japanese myths, had been mistreated by Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess.

Since ancient times, Japanese history has recorded numerous examples of bloody struggles for power and feuds between families, followed by the stories of people who had died as a result of complots and false accusations and turned into vengeful spirits who never stopped grieving their untimely deaths. In Japan, ghosts are first mentioned during the Heian period, in works such as “Nihon Ryōki” or “Konjaku Monogatari”. Later, a new word, goryo, was introduced to designate the spirits of powerful men who died bearing grudges or a desire for revenge and who became ghosts that cause epidemics and destruction.

The beginning of the Edo period marked the golden age of the kabuki theater, when ghost stories became popular. The day of the first performance of a famous ghost story, “Yotsuya Kaidan” by Namboku Tsuruya, became the Day of the Ghosts, which is still celebrated today on July 26. The development of the Japanese theater when hand in hand with the development of ukiyoe (woodblock prints) and the artists started to create more and more ghost images. One of the most well known kaidan (Japanese ghost story) is the “Tale of the Peony Lantern” written by Enchō Sanyūtei, a story that exploits the theme of the sexual encounter with a ghost

Nowadays, ghosts are still a popular subject in Japanese culture, but the imagery has changed from the ghosts without feet who wore the classical kimono. It is my intention today to discuss the development of the ghost motifs and themes, as well as the evolution in the ghost imagery along centuries in Japanese culture.

Renata-Maria Rusu, Babes-Bolyai University

Sakaki – From Myth to Modern Japan

In the Kojiki, the Sakaki tree is mentioned in the episode of the rites observed to convince Amaterasu to come out of the heavenly rock cave. Its role and description in this myth are very interesting. It is called “the true” tree and it is said to have five hundred branches, which become the support of the various sacred objects – the jewels, the mirror, the blue and the white offerings. Then, “liturgies” are recited in the presence of the tree, clearly showing that some king of religious manifestations were associated with it. A similar passage is found in Nihongi, which also includes a passage in the record of Emperor Keikō that mentions the Sakaki of Mount Shitsu, while the record of Emperor Chūai refers to a flourishing Sakaki.

Besides being mentioned by Japanese myths, the Sakaki is present in the life of the Japanese in many forms. It has been used since ancient times in divine rituals, and Sakaki branches are used even today in Shinto rituals as offering wands presented before a kami; they are also used for decoration, as purification implements, or as hand-held “props” in ritual dance. Also, there are a number of festivals in which Sakaki branches are used, such as the Yomisashi Matsuricelebrated every October at Ōmiya Shrine in Iwade Town, Wakayama Prefecture. During this festival, Sakaki sacred branches are carried through the village at midnight, in complete darkness, so that nobody sees them, because they are identified with the kami, and nobody should see the kami in person.

In this presentation, we will discuss the role played by the Sakaki tree in Japanese mythology as well as in modern culture, including photographic illustrations of the use of Sakaki branches in festivals.

Culture and Literature

Iulia Waniek, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

Symbolism of the Boat in Japanese Classical Poetry—an Attempt at Finding Directions

An instrument of discovery or initiation that empowered seafaring nations, the boat is a symbolic element in many important myths. In ancient Egypt the boat was the “vehicle” that enabled the Sun’s journey across the sky, as well as the journey of the souls to the other world. Actually, in the esoteric traditions the boat is often a symbol/instrument of the knowledge beyond death. The ancient Greeks had even come to dedicate temples to ships (on the Black Sea coast known first as the “unfriendly” Pontus Axenios) and to venerate them as a god.

In Japanese myth we have the famous ame no iwabune, from the Jimmu story, as well as some interesting examples of symbolic uses of fune in Manyōshū poems. This paper compares these instances with many other mythological traditions and leaves a few open questions.

The method and ideology that underlies my search is rather similar to the one René Guénon espouses in the “The Holy Grail”, from Symboles fondamentaux de la Science Sacree, namely that myth is not a collective creation, but a really symbolic perpetuation of a much older esoteric knowledge that would have otherwise been lost, unless placed for safety in the oral, collective transmission.

Erin Brightwell, Princeton University

Captured Again: Wang Zhaojun in Barbarian Drama

The creative adaptation and development of Chinese motifs by medieval Japanese writers of prose, poetry, and drama have inspired much study of the place and influence of Chinese literature within the Japanese literary tradition. Often, this has taken the form of comparisons of Chinese “originals” with Japanese “variations.” The present paper, however, seeks to investigate this question from a new cross-cultural angle by considering two works that offer alternative adaptations of a shared Chinese source: the Japanese noh play “Shôkun” and the Yuan drama “Autumn in the Han Palace.”

For their plays, Konparu Gonnokami (active mid-fourteenth century) and Ma Zhiyuan (ca. 1250- ca. 1321) both drew on the immensely popular tale of Wang Zhaojun (Jp. Ô Shôkun), a Han harem beauty married off to a barbarian leader in the first century BCE. At the same time, writing in Muromachi Japan and Yuan China respectively, both authors produced works at vast temporal and socio-cultural remove from their source.

Reading the two plays against each other serves two purposes. First, it challenges the notion that any single adaptation might somehow be a natural result of societal development. More importantly for the present paper, it also highlights the authors’ innovations in unexpected ways, in particular with regard to the impact of Gonnokami’s authorial interventions. “Shôkun” comes to reveal a more sophisticated relationship to its literary origins than has previously been appreciated. These features become clear when the work is brought into comparison with “Autumn in the Han Palace.”

To bring these effects into relief, the present essay addresses three key elements of the staging of Wang Zhaojun’s story. It explores the framing of the story and narrative voice/perspective; the depiction of Wang Zhaojun herself and resultant thematic variation; and the death of the heroine. The final section then considers the overall effect of the juxtaposition of the plays and what it reveals about cross-cultural manipulation of the history and legend of Wang Zhaojun. By bringing the two plays into dialogue with each other across linguistic or political borders, “Shôkun” gains new depth both as a single literary work and as a powerful example of strategies employed by peripheral authors exploring the negotiations of a cultural center with the alien.

Voica Panait, Urasenke Tankokai Belgium

Introduction to Chanoyu and Brief Presentation of Today’s Tea Studying

What is Chanoyu? ”We draw water, gather firewood, boil the water, and make tea”.

Tea was originally brought to Japan from China in the 9th century by the Buddhist monk Eichuu, but the initial interest soon began to fade away. It was not until the end of the 12th century when another monk returning from China, Eisai, introduced the matcha drinking and brought tea seeds back with him. This powedered green tea was first used in religious rituals, but by the 13th century’s Kamakura Shogunate, tea and luxuries associated with it became a kind of status symbol among the warrior class and there began the vogue of tea-tasting contests. During the Muromachi period, Murata Jukou guided tea ceremony in evolving its own aesthetic centered around the concept of wabi— sober refinement and celebration of the mellow beauty that time and care impart to materials.

By the 16th century, tea drinking had spread to all levels of society. Sen no Rikyuu, thought of as the father of today’s Chanoyu, set forward the four fundamental principles: wa – kei – sei – jaku (‘harmony – respect – purity – tranquility’). By following the concept of ichi-go ichi-e ‘each moment is unique’ and perpetuating the above mentioned principles, he led to the full development of the way of tea.

Chanoyu stands on three major pillars: Zen Buddhism, the Chinese I-ching theory and the native Japanese Shinto beliefs.

Three Zen masters were largely responsible for the growth of the tea cult in Japan. Eisai, the founder of Japanese Zen, who brought the tea seeds from China, Doogen who went to China in 1222 to study Zen and brought along a pottery artisan and Musoo Kokushi, who built a simple cottage in a secluded garden for meditation purposes and used the tea as a healthy stimulant.

Having the location, the pottery and the tea itself, not before long a cult developed with the active participation of Zen masters.

The I-ching divination and the system of yin, yang and the five elements constituted the philosophy, cosmology and science of the ancient Chinese people and, after being brought to Japan, it became the framework within which the Japanese people lived for 1500 years.

Shinto beliefs are evident in the symbolic putification of the objects before and after the actual making of the tea.

How is this highly complex Japanese art form perceived nowadays and most of all, how is it studied outside of Japan? I have been studying it for a year now in the Belgium Urasenke school and had the chance to meet teachers and students from all over Europe as well as from New York, Jordan and Hawaii. What are the differences between each continent’s approach? What is the European approach?

I will talk about this based on the philosophical traits above mentioned and I will also talk about the Romanian Urasenke School which gives tea classes in Bucharest.

Round Table: Teaching English/ Japanese: Challenges and Innovations

Chair: Masataka Matsuda

Speakers: Irina Holca, Carmen Tamas, Adrian Tamas, Magdalena Ciubancan

Discussant: Shawn R. White

Keynote address: Yoshiki Hidaka, Nara University of Education

Modernity and Tanizaki Junichiro’s Style Reform: The Thought Process Leading to “kokushi-shumi naishi wabun-shumi“

Tanizaki Junichiro (1886-1965) made his debut in 1910, and stayed active in the first line of the literary circles for the fifty-five years to come, a rare performance for the modern and contemporary Japanese writers. There are many circumstances that could be given as reasons as to why readers continued to appreciate his work throughout the Meiji, Taisho and Showa periods; the main explanation can be found, perhaps, in the fact that, in an age as marked by abrupt changes as the Japanese modernity was, he avoided to lay an excessive emphasis on the consistency of style and subject-matter of his works, and instead changed and transformed them according to the tastes of the different generations. The beginning of the Showa period— the 1930s— is the moment when both the style and the contents of Tanizaki’s works underwent the most dramatic change, and it is about this change that I plan to talk in my present address.

During the above-mentioned period, Tanizaki goes through what is generally known as koten-kaiki, the return to classicism: he publishes numerous novels that have as their background and subject Japanese history, or are inspired by the Japanese classics. This new trend in Tanizaki’s literature is usually attributed to the discovery, or re-discovery, of the beauty of Japanese classics, triggered by his moving from Tokyo to the Kansai area, in the wake of the Great Kanto Earthquake. On the other hand, it must be noted that, at the same time Tanizaki had been showing a keen interest towards topics such as the rapid urbanization of Japan, the advance of capitalist practices in the publishing circles, the pressure exerted by Marxism, and other similar developments challenging the established cultural and literary values. During this period, Tanizaki refers to the artistic value of his works using (in the “Introduction” to Momoku Monogatari, 1932) the expression kokushi-shumi naishi wabun-shumi, which can be roughly translated as “the taste for classical Japanese history or literature”. However, what Tanizaki tried to achieve by turning his gaze upon Japan’s premodernity is neither to merely use historical places and events as background for his stories, nor to imitate the style of the Japanese classics. What was, then, Tanizaki’s purpose when introducing “the taste” for the classical history, language and literature in his works?

In my present address, while looking at the way the Tanizaki of this period positions himself in relation with the Japanese history and classics, I am planning to analyze his literature not so much as a way of reviving the long-gone past, but as an attempt at understanding the essence of the age that we call kindai, i.e., the modern age. The scope of my analysis will include several essays written around the 1930s, such as Jozetsu-roku (1927) and Bunsho-tokuhon (1934); by looking closely at their discursive structure, my purpose is to ultimately make visible the connection between Tanizaki’s ideas about language and literature, and the way he conceived of culture at large.

Language and Culture

Ana-Maria Cojocaru, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

The Japanese Language and the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

The Sapir-Whof hypothesis describes the role that language plays in the the way in which we can interpret reality.

According to this hypothesis, language organizes the world for us and, because it is culturally determined, language encourages a different interpretation of reality focusing on a particular phenomenon.

Language does not only describe the reality but also forms our vision of reality. Language can transmit stereotypes about race, professions, norms, values, etc.

Because I am very interested in the Japanese cultural space, I would like to apply this hypothesis on the Japanese language and in this way I would like to see how the Japanese people see the world and the way they interpret it. Through this approach I believe I can pursue a better understanding of the way the Japanese people perceive the world and I can observe the way in which we can have a better intercultural communication.

Magdalena Ciubancan, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

The Construction of Meaning in Yasunari Kawabata’s Yukiguni

Speech is the defining characteristic of the human species. The final aim of the human linguistic activity is signification, human language being defined as logos semantikos – signifying expression. Semanticity is the constant and the defining feature of human language. The literary text is the space where human language reaches the peak of its functionality, the space where language as logos semantikos fully manifests its creative possibilities. The semantic-functional possibilities of language are reflected in the relations between signs that are found inside the text and their evocative functions.

Our paper is an attempt to analyse the way in which linguistic meaning is constructed in Kawabata’s famous novel Yukiguni (Snow Country). The meaning of a text and especially the meaning of a literary text represents much more than the sum of the meanings of its composing elements. We need to search for relations that go deeper than the mere syntactic combinations of words and phrases. The theoretical basis for our analysis is provided by the view of the Romanian semiotician Carmen Vlad on the reticular character of textual meaning (Vlad, C. 2003. Textul aisberg. Cluj-Napoca: Casa Cartii de Stiinta). She claims that textual meaning is the result of the interaction of sixteen linguistic networks:

- The grammatical network (the syntactic-semantic basis)

- The actantial network (the relations between the actants)

- The communicative network (the polyphony of voices)

- The referential network (the relation between verbal or non-verbal signs with the extra-linguistic reality), with two sub-categories – the extra-linguistic and the intratextual networks

- The thematic network (the relation between old and new information)

- The illocutionary network ( the typology of speech acts)

- The argumentative network (persuasive effects, intentions, opinions etc.)

- The spatial-temporal networks (the spatial and temporal configuration)

- The event-episode network (the narrative configuration)

- The sememic network (the text isotopy reflected in semantic marks)

- The figurative network (figures of speech)

- The modal network (stylistic features, ways of using the language)

- The melodic and the phonemic/graphic network

- The intertextual, metatextual and paratextual network

We look at Kawabata’s text trying to identify the active networks that play a part in constructing the meaning of the novel, with special emphasis on the sememic network. We will refer to the original text and to its translations into Romanian and English in order to see which of the networks become active in each of these languages and how the activation of one or another of the networks may influence the final result.

Ioana Banner , University of Bucharest alumna

About Japanese Proverbs: A Comparative Analysis with English and Romanian

Why Japanese proverbs?

Trying to study a foreign culture represents an attempt to better understand our own cultural background. First fascination comes from differences. However, in the case of cultures that had developed so far apart in distance and time, like Japan and Romania, similarities are most astonishing.

Thousands of years of wisdom of a people are concentrated in the proverbs. This is why the similarities between Japanese and Romanian proverbs are the starting point of this study.

About this paper

With this paper I have tried to identify the most important aspects of the proverbs and discuss them in the four chapters as follows:

The first chapter, Metaphors in Japanese proverbs, concentrates on the most important symbols that construct the proverbs. I have analyzed not the meaning of the proverb as a whole, but the elements of reference.

This chapter is an analysis of metaphors in Japanese proverbs in comparison to the metaphors used in English and Romanian proverbs.

In the second chapter, Japanese proverbs of foreign origin, I have tried to identify the main sources of proverbs adapted from other cultures. Buddhism and Confucianism are the two main sources of inspiration for the Japanese.

We can say that, at present, Buddhism and Confucianism are a closed source of inspiration for Japanese proverbs. However, the relation with Western culture is a much newer one and there numerous things that Japan does not know about the West and the West does not know about Japan. Japanese proverbs of Western origin are an open source in the sense that there is a strong posibility new proverbs will be created in the future.

In the third chapter, Proverbs without correspondents in English and Romanian, the focus is on the elements that are specific to Japanese culture, that cannot be found in either English or Romanian proverbs, that originate in the culture of Japan: Japanese religion, tea, calligraphy and so on.

Besides Japanese traditional elements I have tried to identify specific images in Japanese proverbs. For example:「磯の鮑の片思い」(Iso no awabi no kataomoi – The unrecognised love between the beach and the shell) is an example of unshared love. This kind of image cannot be found in either English or Romanian proverbs.

Humor has a major role in both English and Romanian proverbs. The situations when one would use a proverb to make the ones around him or her laugh are very common. In the fourth chapter, Humor in proverbs, I wanted to see whether this is valid for Japanese proverbs as well.

I have seen that, in the proverbs, humor is concentrated, in most cases, on funny images. Wordgames, very common in English and Romanian proverbs are totally inexistent in Japanese proverbs. The Japanese laugh at the image they make in their mind after hearing a certain proverb.

The proverb「頭を隠して、尻を隠さず」(Atama wo kakushite shiri wo kakusazu – To hide your head but to leave your bottom unhidden) is a classic example of Japanese proverb humor.

In the end of the paper I will try to demonstrate how Japanese proverbs can be used in order to teach Japanese culture classes to foreigners interested in Japan.

Image and Text

Chie Nakane, Aichi University

On the Illustrations of Kokonchomonjyu

It is known that the original book of “Kokonchomonjyu” was first published in 1690 (Genroku 3), and the second edition was published in 1770 (Meiwa 7). There are two versions of “Kokonchomonjyu”, i.e., the Genroku version and the Meiwa version. In this presentation, I will talk about the Genroku version of “Kokonchomonjyu”. In particular, I will focus on the process of editing pictures in “Kokonchomonjyu”.

“Kokonchomonjyu” is composed of twenty volumes comprising 726 short stories. Tachibana-no-Narisue compiled it in 1257, Kamakura era. At first, it did not have any pictures. Later, in the Edo era, some pictures were added to the Genroku 3 version, which represents the focus of my presentation today. Five pictures were added to selected stories from each volume and, as “Kokonchomonjyu” has twenty volumes, there are one hundred pictures in it.

First of all, we have an important problem. The cut-in illustrations of “Kokonchomonjyu” (the Genroku 3 version) do not show a clear correspondence with the context where they were inserted. Therefore, I should clarify what scene of each cut-in illustration of “Kokonchomonjyu” (the Genroku 3 version) represents. For instance, I will show you some examples of volume 2. In one picture, there is a warrior with a spear on the right side, and something small on the spear. On the left side, there is a big tree, and the warrior is in the tree. According to my interpretation, this picture shows Shotokutaishi and Moriya fighting over the belief in Shinto and Buddhism. The small figure on the spear is Shitennou, who supports Buddhism. The big tree on the left is a hackberry (enoki), the warrior in the tree being Moriya, a defender of Shinto.

Volume 2 does not have any other battle scenes except this one because the stories concerning Buddhism were compiled for volume 2, so we can safely assume that this picture is for the 35th story of volume 2. Besides, the second picture (which follows this one) refers to the same story, because it also depicts the scene of a battle.

The third picture shows a monk on the right and a dragon on the left. Volume 2 has only two stories with dragons, which means this picture must be for the 42nd or the 60th story.

The fourth picture has a monk on the right, a woman at the center and a man or a woman on the left, which suggests that it might be a holistic picture for all the stories in volume 2. It thus becomes clear that some pictures are attached to specific stories, while others do not correspond to any particular story. My presentation will focus on images that are specifically related to a certain story.

Kazuaki Komine, Rikkyō University

Looking at Tales on Buddha’s Life and Their Related Images: About the World of Mount Sumeru as Depicted in the Shaka no honji

Tales and stories about Buddha’s life spread throughout Far East Asia along with the generation and development of Buddhism. In Japan, these tales gave birth in the 15th century to a work called Shaka no honji, which belongs to the category of the Otogizōshi, and which inspired a great number of picture books and scrolls until the 19th century. Taking the Shaka no honji as the main object of study, I would like to examine in this paper the general relationships between images and tales.

For example, the Shaka no honji tells us that the queen Māyā, Buddha’s mother, who died one week after giving birth to Buddha, was reborn becoming the summit of Mount Sumeru, or in other words, the celestial world. Then there is a dramatic scene where the enlightened Buddha, wishing to give a lecture to one of his disciples, took him to that celestial summit, and then met with his mother.

In another place the book depicts the all-out battle between Maugdalyayana, a disciple of Buddha, who transformed himself into a dragon, and Devadatta, the old enemy of Buddha, who, along with some unbelievers, was trying to block Buddha’s ascension to Heaven.

Both of these scenes are set in Mount Sumeru, that is to say, in the center of the Universe. In this study I would like to focus on these two episodes, and at the same time inspect their related pictures, because images have a potential of expression that cannot be rendered in words. Examining the mutual relationships between these two ways of expression, I intend to pursue the true meaning of the Japanese tales of Buddha.

Angela Dragan, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

Word and Image in Santō Kyōden’s Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki江戸生艶気樺焼

Santō Kyōden山東京伝 (1761-1816) is known today as a gesaku writer of the later 18th century. He was also active, however, as an ukiyo-e illustrator under the name of Kitao Masanobu北尾政演. The breakthrough in his career came in 1782, when Ôta Nanpo大田南畝in his gesaku critique, Okame hachimoku, ranked Masanobu as an ukiyo-e artist in second place after Torii Kiyonaga. Nanpo also praised Kyōden’s kibyōshi, Gozonji no shōbaimono 御存商売物, which the author had illustrated under his artistic pseudonym, and cited both text and illustrations for their excellence. But it was Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki that brought him fame. Its main character, Enjirō艶二郎 who aspires to be an Edo playboy and its broad flat nose, botan no hana 牡丹の鼻, illustrated by Kitao Masanobu, became one of Kyōden’s trademarks.

We thus see that Santō Kyōden/Kitao Masanobu acted as a creator who reached high skill in two professions, both as an artist and as an author. Kibyōshi, known for their balanced blending of text and image, in many ways represented the best medium for Kyōden to express both of these skills.

Enjirō, the son of a wealthy merchant, dreams to become a true connoisseur, a tsū通. How to behave in the red light district, how to dress like a man of the world or how to hold a proper conversation were considered some of the standard requirements of the time. However, a true connoisseur needs more than this, he needs a reputation. But nor his physical appearance, neither his wit help him achieve this. So relying on his father’s money, he sets upon a true journey to get the reputation of a tsū通. He pays a prostitute to pretend to be jealous of him, to harass him or to gossip about their supposed love affair. Moreover, he asks his parents to disinherit him because all of these and he even attempts to commit a love suicide 心中with a courtesan that he paid. Text and image as well follow the comic story of Enjirō and his foolish adventures and build at a narrative level and visual level a complex story that reveals the world of Edo.

My presentation on the kibyōshi Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki will analyze how text and image work together in forming a coherent whole, arguing that it is the remarkable interaction of these two elements that won its author such high praise.

Guest Speaker: Shuji Ikuta, Nara University of Education

Education about and against Discrimination in Japan: Regarding Dowa Education and Human Rights Education

The aim of my speech is to discuss the history of Japanese human rights education (HRE) and to indicate several approaches for analyzing its characteristics, while taking into consideration the position of Japanese HRE in relation to relevant educational fields.

HRE has been discussed in Japan since the 1990s in three phases: the UN Decade for HRE (1995-2004), the official introduction of a “Period for Integrated Studies” in school since 2002, and the official end of the national Dowa policy (liberation and integration of Japanese discriminated communities) and education in 2002. Especially, the Japanese HRE has been historically influenced by Dowa Education (education for the integration of Japanese minorities).

The origin of Japanese HRE lies in the Yuwa education and the Dowa education as educational measures for solving the “Buraku problem” in the modern Japan after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. After World War II, the Dowa policy including Dowa education was acknowledged as “an important national task to solve in Japan” in the report of the Council for Dowa Integration Measures to the Prime Minister in 1965. It was implemented from 1969 until March 2002.

In 2003 a “Work Group for the Investigation and Cooperation about Learning Guidance and Methods of HRE” was organized by the Japanese Ministry of Education. It stated that it was important for HRE programs “to develop people’s sensitivities so that when they encounter violations of human rights in their daily life they would feel very intuitively that they are dealing with an instance of wrong-doing, and to arouse such a spirit of human rights as to prompt people to take attitude and action based on human rights unconsciously in daily life.”

Table : The Place of HRE (Japan)

| Orientation Value/ Individuals | |||

| ViewRelation | Moral Education | Law-related Education | System |

| HRE in JapanDowa Education | Multicultural Education | ||

| Task/ Group | |||

As can be seen in the table above, “The Place of HRE (Japan)”, the Japanese HRE has a strong orientation towards equality as a relational concept, and from a “sociological” perspective, in which human rights problems are grasped as mentality problems. I want to clarify the Japanese characteristics of HRE by using several analyzing approaches.

When considering the future of HRE in Japan, it must be said that there is a strong necessity to cultivate the programs that emphasize the relation between the dignity of individuals and the system of laws, and the empowerment of individuals. In this sense, HRE should learn more from relevant fields such as law-related education and multicultural education, and develop a systemic comprehensive approach, incorporating it into the Japanese education system.

Guest Speaker: Masaru Tongu, Nara University of Education

Shinto, the Way to the Gods: Fundamental Healing Practices in Japanese Religion

The word “religion” has been translated as “shukyo” in Japanese, but the shrine-related indigenous beliefs have been termed not “Shinkyo” but “Shinto”. The word “to or michi” is also used to refer to Japanese traditional arts like “Sado”, “Shodo” or even “Judo”. Many Japanese sometimes refer to Buddhism as “Butsudo” instead of “Bukkyo”. Then again, the Japanese translation for the word “shrine” is “jinja”, a term made up of the word “god” and “sha” as in “kaisha”, a very non-sacred contemporary business organization.

These examples bear apparently simple explanations, yet things are not quite as clear as they seem if we seriously try to give satisfactory or persuasive answers to them. Therefore, I would like to propose the hypothesis that the key to those questions might lie in the religious mind of the ancient people, who had based their beliefs on nature observation. In this presentation, I would like, starting from the original meaning of Japanese words such as “michi”, “yashiro”, “akai”, or “kuroi”, to reconstruct the ancient people’s representation of life and death, which has become the basis of Japanese religion.

My presentation will focus on the following points:

(1) Every living thing instinctively understands that in nature, time consists of a cyclic repetition of darkness and light.

(2) In the old times, people seem to have thought that the smooth repetition of one day, one month and one year leads to a natural cycle which provided food and order in the known universe.

(3) Likewise, aging without any visible damage to the physical body would ensure safe passage of the human body to the world of spirits and vice versa.

(4) Curing and healing in this context are performed in order to simply remove any mental and physical incurred in this world, which might become an obstacle to the smooth transition towards the other world.

History and Culture

Andrea Revelant, Department of Asian and North African Studies, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

Towards a New Conception of State-Society Relations: Fiscal Policy between the World Wars

By the 1920s, Japan seemed well on its way to completing a transition from an oligarchic regime to a parliamentary system of government. However, party cabinets established in the interwar period had to cope with a set of national problems that required an increased effort for the preemption of social conflict and the mobilization of popular support to implement state policies. Failure to achieve these objectives can be considered one of the concurrent causes of the eventual demise of party politics and shift of leadership to the military and bureaucratic elites in the 1930s. What went wrong? The case of interwar Japan may provide useful reference for the study of contemporary world politics, as it shows that processes of democratization are by no means irreversible, but rather subject to many contingent variables. This paper will focus on fiscal policy, particularly the question of tax reform, as a topic which offers ample ground to explore the interaction among party leaders, career bureaucrats, organized interest groups and society at large.

In the wake of World War One, the fiscal system that had sustained the modernization of Japan since the Meiji era was showing evident signs of distress. Conceived primarily to finance state investment and foster industrial growth, taxation had developed serious flaws in terms of equity: in a horizontal perspective, the shift of burden from rural to urban communities did not sufficiently reflect the latter’s superior capacity; on a vertical axis, the prevalence of regressive and proportional imposition went to the disadvantage of the lower income classes. Local taxes were especially unfair, as the central government required lower administrative levels to perform increasingly costly functions without releasing its control over the most efficient fiscal resources. These problems became a major political issue in the climate of social and economic unrest of the 1920s, giving rise to heated debate on what measures should be taken to redistribute the burden.

Though scarcely treated in historiography, the tax reform plans that successive cabinets laid out and partially implemented through the interwar period provide insight into how political elites tried to redefine their approach to public finance, working out a compromise between vested interests and popular demands. A comparative analysis of guidelines set by the two main parties, in particular, brings to light that divergent policy choices depended on differences in their social base, as well as in their relationship with the bureaucracy and business circles. Period sources indicate that discussion between and within the parties was more complex than it is often acknowledged; they also contain evidence that party cabinets effectively kept under check bureaucratic initiative, which later became the main driving force in the general reform of 1940. In conclusion, the paper will attempt a comprehensive assessment of fiscal policy in the period in question, pointing at the signs of integration of the masses into the political process, but also at the limits of this change and their consequences on Japan’s institutional order.

Giovanni Borriello, University of Bergamo

The Long Trip of the Jennerian Vaccination from Europe to Japan

Before the introduction of vaccination, cowpox was considered one of the greatest plagues of mankind. It was endemic worldwide and periodically erupted in lethal epidemics. In the late 18th century only in Europe 400.000 people died annually.

With the introduction of the Jennerian vaccination cowpox incidence steadily began to decline during the 19th century. Actually the publication of Edward Jenner (1749-1823), An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of The Variolae Vaccinae. A Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Countries of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of Cow Pox, in London in 1798 represents an important milestone for the control of this infectious disease.

However, during the 19th century this aim hasn’t been fully achieved. Violent epidemics continued to erupt periodically.

In countries far from Europe as for example in Japan, the use of the vaccination became a further step in the complete adoption of Western medicine.

Nowadays it is believed that the origin of cowpox was in India and from there it spread toward West in Europe and East in China and Korea.

As far as the origin of cowpox in Japan, the situation seems rather complex. For example, Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866) referred to two possible origins, the first dates back the first epidemic to 626, the second, more reliable to 735. According to the first text, the cowpox was carried in Japan when because of a bad harvest rice and barley were imported from Korea. In the harbor of Ōsaka, on one of the 170 ships, three men were infected by cowpox. The epidemic of 735 was carried to Tsukushi (Kyūshū) by a fisherman of Silla, the ancient kingdom of Korea. The epidemic called sekikansō lasted for about 2 years and caused high mortality.

During the 8th century cowpox was endemic in Japan and periodically caused epidemics.

It should be emphasized that cowpox made no distinction of class: nobility and poorer social classes were equally victims of its virulence.

However, in general, Government did not impose any prevention measures till the end of the 19th century. Common people believed that cowpox was a kijin-byō, a disease caused by a malevolent spirit. In this case it was the spirit of cowpox, the hōsō no kami. Fearing the attack of this malevolent spirit, people abandoned the unlucky individuals infected with the disease. In his works, Von Siebold refers to the restrictive rules as well adopted in Kyūshū, that imposed the quarantine and the complete isolation of the people suffering from the disease in distant and inhabited zones.

In this paper, through the analysis of the accounts of journeys written by some European medical officers in service on Deshima during the Tokugawa period, we discuss about why were the Japanese physicians so interested in Jennerian vaccination and in which way the Western medical techniques to vaccinate spread in Japan despite all the problems related to the great difficulty to procuring the vaccine.

Andrada Butnaru, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University

From Concrete to the Tree: The Journey of Post-World War II Japanese Architecture

Western influences

The Modernist Movement with its “5 points of architecture” (freestanding support pillars, open floor plan independent from the supports, vertical facade that is free from the supports, long horizontal sliding windows, roof gardens) found a similar background of constructive concepts in Japan and was adopted after World War II. It introduced a series of changes in the materials and techniques of construction, with the appearance of concrete, steel, large panes of glass and prefabricated structures. It also changed the scale of buildings (high-rise), added new architectural programs and modified the existing ones.

The most representative architects that adopted this style were: Kunio Maekawa, Kenzo Tange, Kiyonori Kikutake, Fumihiko Maki, Kisho Kurokawa, who added to this International style Japanese features, such as the invisible tradition in the case of Kurokawa, and developed in the 1960s 4 neo-modern movements: structuralism, contextualism, symbolism and metabolism, with its international symbol, the capsule.

The Postmodernist Movement, with its historical orientation, appeared in the 1970s particularly in the buildings of Arata Isozaki, who drew inspiration from several previous European architectural styles.

High-tech architecture, which incorporated elements of high-tech industry and technology into building design, manifested in Japan in the 1980s through the works of Shin Takamatsu.

Traditional Japanese influences

During the 1960s there were also architects, such as Kazuo Shinohara, who formed a so-called “Shinohara school” and rejected the neo-modern movements. He sought inspiration in traditional architecture, interpreting its concepts in terms of space, abstraction and symbolism.

Starting with the late 1970s, Tadao Ando explored the idea of promoting local or national culture within architecture, as a reaction to the homogeneity of Modernism. He implemented the Buddhist concept of symbiosis of humans and nature and reacquainted the Japanese buildings with the outside, through traditional elements such as the engawa. His architecture is characterized by the use of natural elements, light and water, but also concrete as a pure part of construction which also enhances nature.

In the late 1980s, the followers of the “Shinohara school”, such as Toyo Ito, became interested in the urban life and the contemporary city and integrated in their buildings natural elements with those of technology.

During the last 2 decades, Ito, SANAA, Shigeru Ban, Kengo Kuma and more recently Sou Fujimoto and Junya Ishigami, to name just a few, have explored new ways of recovering the tradition of Japanese buildings and reinterpreting it for the 21st century, especially the inside-outside relation and the Zen Buddhist concept of ma (the space in between) through transparency, reflection, flexibility and fluidity of space, box in box in box and the building like a tree / forest concepts.

To sum up

Compelled by the circumstances at the end of World War II, the Japanese adopted the Western materials and ways of construction, only to later return to tradition, by enhancing the outside world while at the same time developing a teacher-student relationship between nature and humans.

Modern Literature

Kayo Sasao, Ryugoku University

Higuchi Ichiyo’s Takekurabe: Its Reception in Connection with Post-war Education

Higuchi Ichiyō’s Takekurabe was written between 1895 and 1896, and is the short story that established Ichiyō as one of the prominent writers of the Meiji era. One interesting fact about Takekurabe is that, nowadays, it is considered, among all of Ichiyō’s works, the most appropriate for children to read. While the reviews it received at the end of the 19th century were all excellent, it must be noted that Takekurabe has only started to be regarded as a great example of literature for children 50 years after publication, in the wake of the Second World War. Until then, given the fact that the story takes place near the pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara, and that the young protagonists are described in close connection with that environment, it had been consistently shunned, and labelled as inappropriate reading for children. What, then, brought about the post-war re-evaluation of Takekurabe?

One clear proof of the new position of Takekurabe as literature worthy of children’s eyes after the war is the fact that it was included in the textbooks published during the late 40s and early 50s. During the same period, it was transformed into a book for children (by Muramatsu Sadataka, from Sansui Shobō, 1948), made into a movie, at the recommendation of the Japanese Ministry of Education (from Tōhō Company, 1955), and turned into a comic book by Takeda Masao (Shuei Publishig House, 1955). The problems faced by the “translation” process (be it between classical and modern language, or between two different systems of expression, i.e. text and image) include, on the one hand, the difficulties of transposing old Japanese into modern Japanese, in order to make the novel accessible to a larger number of readers. On the other hand and on a deeper level, one issue that needed to be addressed while turning Takekurabe into a piece of literature for children was the necessity to find a suitable solution as far as the location of the story, the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter, was concerned.

One of the reasons why Takekurabe was considered as a good reading for children is the fact that “school” played an important role in the story. While describing the way children were traditionally divided into groups according to what part of town they lived in, it also lays great emphasis on the way “school” encourages new bonds to appear between them. It is thus safe to assume the image of “school education” as presented in Takekurabe is one of the main reasons why the novel was introduced in post-war textbooks, and considered educational for young audiences.

By taking up the topic of the rewriting of Takekurabe as children’s literature, I am planning to clarify the way Ichiyō’s novel was re-evaluated in the context of post-war democracy and in connection with the implementation of the coeducational system. My analysis will shed light on the process of “self-examination” Japan had undertaken after the war, with some of the problems it revealed, or, conversely, concealed.

Irina Holca, Osaka University

Self-perception and Self-projection: Japan in Okakura Kakuzō’s The Book of Tea and Its Translations

The Book of Tea, written in English and published in New York in 1906, has been translated over the years into more than thirty languages, in some of them even before it was translated back into the author’s native Japanese. The first Romanian translation dates back in 1925, and a new one was published in 2008. ven today, The Book of Tea is often included in the list of reference books for students of Japanese studies, together, for example, with Ruth Benedict’s The Chrysanthemum and the Sword or Takeo Doi’s The Anatomy of Dependence. At the same time, in Japan, The Book of Tea circulates widely as a bilingual book, to be used for the study of English, but also as an introduction to “the heart of Japan”.

Okakura Kakuzō (Tenshin)’s writing of The Book of Tea at the beginning of last century is related to the fact that the emerging modern Japanese state had just fought and won the wars against China and Russia; it also coincides with the publication of other books by Japanese writers for foreign audiences, i.e. Inazō Nitobe’s Bushidō: the Soul of Japan (1900) or Uchimura Kanzō’s Representative Men of Japan (1908). In my presentation, I will analyse the first translation of The Book of Tea by Muraoka Hiroshi (1929), focusing on the meaning of the twenty-year gap between the publication of the book in English and its introduction to Japan. I will also touch upon this translation’s revised editions (1938, 1939), clarifying their relation with the celebration of 2600 years from the enthronement of emperor Jinmu. Finally, I will look at Asano Akira’s translation published in the post war period (1956). For comparison, I am planning to bring up Nitobe’s Bushidō, as Tenshin criticizes in his work the tendency of the West to appreciate Japan’s “art of death”, as he calls bushidō, instead of paying more attention to Teaism, which he considers to be “the art of life”. Bushidō’s first translation into Japanese dates from 1908, and its re-translations and re-publications also seem to focus around the year 1938.

By comparing and contrasting the different versions against their different historical/ political/ social backgrounds, I intend to shed light on the way the domestic and international perception of “Japanese-ness” has been transformed/ transforming throughout Japan’s modern history, in order to ultimately try to initiate a discussion about the present-day situation.

I plan to focus on the role that “translated texts” have played in molding Japan’s modernization, at the same time analyzing the background forces (economical, political, cultural) that, in their turn, have shaped the “translation” at different points in time. Through my analysis, I especially want to look at how the internalization of otherness influenced self-perception and national identity, and vice versa.

Masataka Matsuda, Osaka Electro-Communication University

A Study of the Wartime Poems of Shinkichi Takahashi: Writing between Dada and Zen

Tristan Tzara (1896-1963) writes: “No one can escape fate. No one can escape DADA. Only DADA can make you escape fate.” Most of dadaist expressions are thus beyond our rationalistic understanding, yet some of the avant-garde statements can be occasionally interpreted when paralleled with non-logical wording of Zen philosophy. I must confess that my knowledge of Zen is limited and I have never had a Zen master’s guidance, that is why I do not claim to offer any essential insights into the world of Zen. However, passages from explanatory writings about Zen often help understand some aspects of modern art whose purpose can be said to be “making the common uncommon.”

Dada was previously considered as the picture of inaccessibility, incommunicability, incomprehensibility, as Tzara himself writes: “Dada does not mean anything,” which often made people confused and even frightened. Despite/because of the public disturbance, Dada still has its own singular status in the aesthetic discourse of modern art though it has already been institutionalized (the comprehensive museum exhibition of Dada art was held in Pompidou center in 2005-2006, National Gallery of Art in Washington in 2006, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2006), or I can even say “neutralized,” into academic fields. In this presentation I would like to feature Dada from a different viewpoint by examining the writings of Shinkichi Takahashi (1901-1987), who is often called “the first dadaist poet in Japan” and “a Zen poet” as well.

In Collected Follies Takahashi writes: “I am not a man nor even anybody. If someone who reads the things written here tries to attribute to me the responsibility for placing these words in this manner, that will not be a right thing to do because I will already have become another man at that moment, inevitably.” His awareness of an art of writing beyond language, which might have engaged him in Koan (conundrums for Zen meditation) and eloquent “nothing” in Dada, became thrillingly acute especially in his wartime writings, where he could not write what he wanted to because of the excessive censorship in Japan. And this period of time must have been very important to Takahashi as a meditative occasion to cultivate a better understanding of Dada and Zen or to reach another state of enlightenment. In this presentation, therefore, I will select some of his wartime writings (including his controversial pro-war poems) and think about his way of writing between the lines.