Below are the abstracts of the papers given at the first edition of the conference. We had numerous sessions about culture, literature and linguistics, and 20 participants from 7 countries.

Day 1

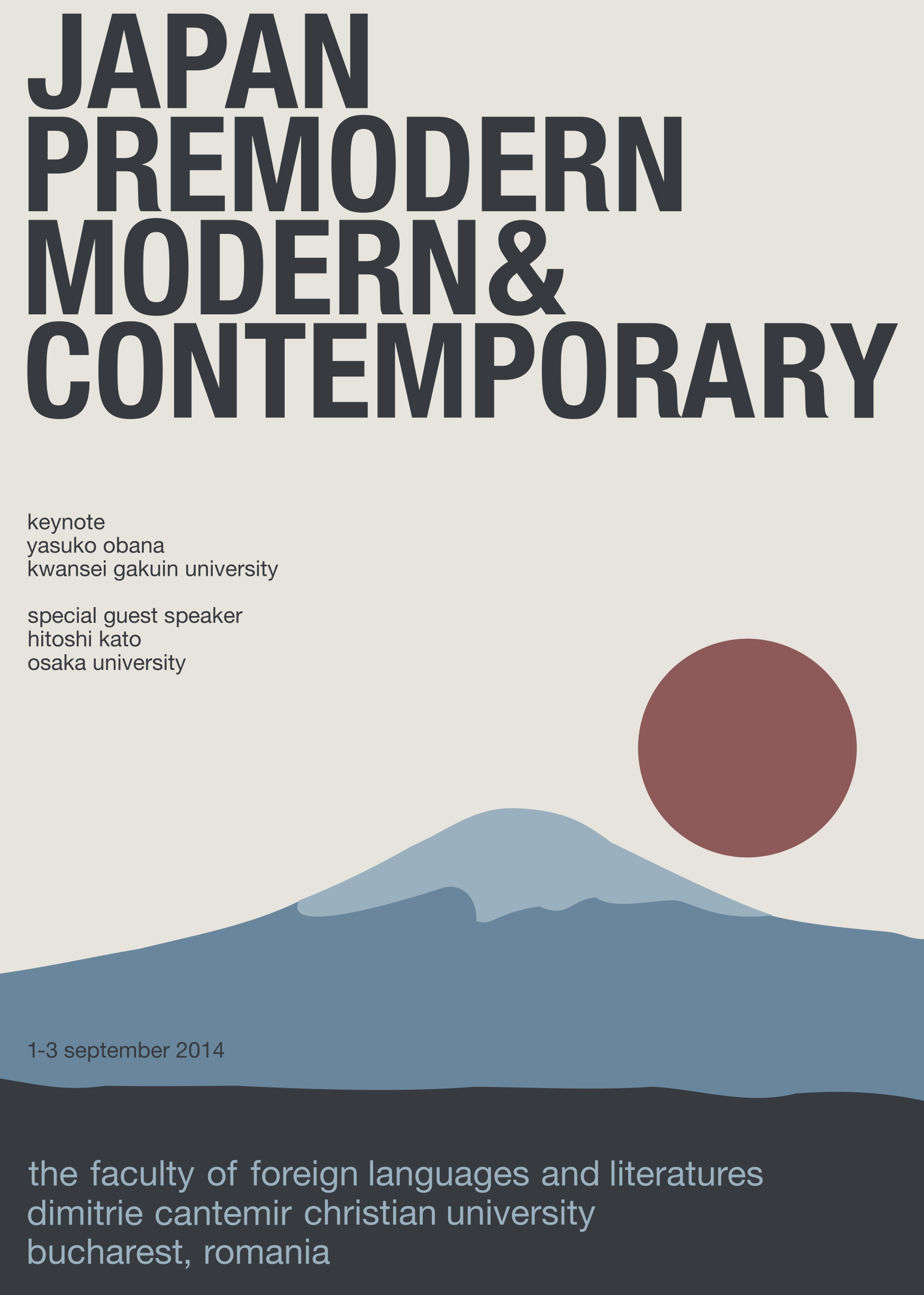

Keynote speech: Yasuko Obana (professor, Kwansei Gakuin University, School of Science and Technology) Routine Formulae in Japanese: Social Conditions and Constraints on Their Use

Routine formulae such as greetings and set phrases are stereotyped clichés in every day conversation. They are often called ‘phatic communion’, which was coined by Malinowski (1923), because they do not convey particular information or address enquiries to get necessary information (i.e. report talk), but aim to establish communicative harmony between participants in conversation (i.e. rapport talk). They are also called ‘small talk’ or ‘grooming language’. However, their social functions and effects are not as small as those names imply. Their absence may jeopardize friendship, their misuse may cause conflicts and misunderstandings, and the wrong timing of their use may ruin the flow of conversation.

I will introduce a few examples of routine formula in Japanese such as konnichiwa, yoroshiku onegaishimasu, sumimasen as a replacement of thanks by analysing their pragmatic conditions and constraints, and demonstrate that they do not occur at random but carry the speaker’s social roles in relation to the other participant. Unlike simple greetings such as ohayoo gozaimasu (good morning), which can be used by anyone to anybody when a morning greeting is expected, those routine formulae are the linguistic implementation of one’s roles and should be used only when such roles are recognised among the participants. For example, konnichiwa is a greeting when strangers meet, or when acquaintances meet in a street, but cannot be used to family members or close friends. High school students do not use it to their teacher when they meet her/him at the corridor in the afternoon. This greeting cannot be used at random like ‘hello’ in English. This is because konnnichiwa constitutes certain pragmatic conditions, which then cast certain roles to the participants. Konnichiwa occurs within the domain of such roles.

‘Roles’ used here come from a theory in social psychology, called ‘Symbolic Interactionists’ Role Theory’. Social roles are equivalent to one’s identities and identities are created and processed in talk-in-actin rather than a social given. My recent research in pragmatics is based on this theory. However, in this talk I will provide socio-cultural backgrounds conditions of certain routine formulae rather than go into the details of this role theory.

Magda Ciubancan (lecturer, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University) Greeting and Leave-Taking in Japanese and Romanian

An important part of our everyday interaction with others, greeting expressions are often taken for granted and used automatically, while their semantic content is almost forgotten or ignored. The importance of the role that greetings play in human societies is, however, undeniable. Were it not for greetings, human relations would not develop smoothly, as one of the main roles that greeting expressions play is that of eliminating possible tensions from the communication between people. The way individuals relate to each other is determined by very complex rules of culture and behavior. These are learned – not acquired – at an early age and it is the speaker’s ability to match routine expressions with particular cultural and socio-historical circumstances. Starting from Edward Hall’s distinction between high-context cultures and low-context cultures and from the corresponding characteristics of each type of culture (Hall, 1976), I analyse the role that context plays in various types of greetings in Japanese and Romanian. While Japan is given as a typical example of a high-context culture, the case of Romania still needs to be investigated. My paper is an attempt to demonstrate that, when one takes into account the role of context in communication, the distinction high/low should not be regarded as a clear-cut dichotomy, defining opposing spaces, but more as referring to the extremes of a continuum on which certain segments are activated at certain times.

Andreea Sion (lecturer, Hyperion University) Information Packaging in Japanese News Lead Sentences

News stories are reports about recent events or happenings, that must efficiently convey accurate, clear and unambiguous information to a mass audience, in a short amount of time (if broadcasted) or space (if written). This study aims to analyze, from a discursive standpoint, the way in which information is conveyed in the news first paragraph, usually named “lead”, in terms ofinformation packaging (as defined by Prince 1981) and referent identifiability (as defined by Lambrecht 1994), simultaneously taking into account several factors, such as the type of media (broadcast /vs./ written news), the type of grounding provided for the subject noun phrases found in the lead sentences and the way the subject noun phrases are linguistically marked (as topics or non-topics).

Ljiljana Markovic (professor, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philology) Japan—In Quest of a New Paradigm of Modernisation

Novel possibilities made available by the process of digitalizing the cultural heritage and digital resources pose the need for a fresh, all – round view of culture and formulating a new paradigm of comprehending the cultural heritage as well as for understanding contemporary cultural endeavors as a new task set before researchers. Effects of digitalization are considered in a holisitc manner, with a special emphasis on the experience of Japan, where rapid social, cultural and economic development has been achieved and which could be referential in considering a model of development and a new paradigm of modernization within which digitalization assumes the role of a Keynesian multiplier. Barrington Moore concludes that the development of modernization can be reached on three different paths. One road is the capitalism democracy; Moore calls it the “bourgeois revolution, which was the road that England took through the Puritan Revolution, the French through the French Revolution, and the United Stated through the Civil War. The second route is the capitalist route, which was the development that took place in Japan and Germany. Moore points out “in the absence of a strong revolutionary surge, it passed through reactionary political forms to culminate in fascism”. The third road is communism, were the main driving force of the revolution are the peasants e.g. China. Moore’s studies of the three different “social origins” of modern nations reaches the conclusion that in those countries where the middle-class was the driving force of the revolution, e.g. England, democratic institutions emerged and resulted in a democratic capitalist society. However, in those countries were the revolts came from the peasant, or the top, the democratic institutions did not emerge and resulted in fascist state-capitalist societies. In the case of Japan, “the adaptability of Japanese political and social institutions to capitalist principles enabled Japan to avoid the costs of a revolutionary entrance onto the state of modern history.

Iulia Waniek (professor, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University) Ame no Iwabune, Amakudari, Hagoromo setsuwa – Instances of a Permanent Communication between Heaven and Earth

There are many elements in Japanese mythology – ame no iwabune, ame no ukihashi, ama kudari, hagoromo no tennyo for instance – that point to the existence of a religious thinking which induced the ancient Japanese to perceive Heaven and earth, or this world and the world of spirits, as being in constant contact, communication, and even contiguity. Joseph M. Kitagawa’s essays (such as “Reality and Illusion: Some Characteristics of the Early Japanese ‘World of Meaning,’ ” Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 11/1970: 5-10) show that the early Japanese world was a “one-dimensional monistic universe”, that is, the three realms of the High Heaven, the Manifest World, and the Nether World were interchangeable, or interconnected. As Kitagawa put it, “Even the gulf between the world of the living and the world of the dead was blurred by the frequent movement of spirits and ghosts and by other channels of communication between the two realms, such as oracles, fortunetelling and divination. In other words, the world of early Shintō had a unitary meaning-structure, based upon the kami nature pervading the entire universe, which was essentially a “sacred community of living beings “all endowed with spirits or souls.”

In this paper we will look at some instances of ama kudari by means of (ame no) iwa fune, which “left their traces” in several jinja from the Nara-Osaka area which have iwafune in their name, and among their relics or sacred land marks. Romanian mythology also has places where the primordial founders of the land descended and founded their thrones or altars, and also places such as forests, caves, ravines, where supernatural beings (like the female yele or sanziene) can be encountered. However, if the descent of tennyo, who sometimes stay on earth and marry a villager, is beneficial to the humans, just like the descent of Urashima no ko, or the voyage of Tajima Mori to Tokoyo no kuni, the intrusion into the human world of the yele and other such supernatural beings is ominous and dangerous. In the Japanese tradition there are much more such instances of contact, and they are mostly instances of beneficial contact to the humans. The ancient Japanese seem to have lived in deep harmony with the less understood forces of nature.

Liu Xiaoyan (doctoral candidate, University of Heidelberg): Bringing Modernity to New-born Republican China: A Case Study on Japan’s Inspiring Role in FunüShibao

The anti-imperial Qing Court Revolution of 1911 failed to deliver on its promise of restoring a strong China. It nonetheless ushered in a new era that brought new modes of knowledge migration. The development of a commercial periodical press, those addressed at a female audience in particular, was one of the by-products of the 1911 Revolution. While Western knowledge was widely recognized to have played an enlightening role in helping “to open the eyes” of the Chinese population, the significance of Japan as the first modernized East Asian country and hence as a carrier of Western knowledge was not fully recognized. Funü Shibao 婦女時報 (1904–39), one of the women’s magazines that witnessed the several crucial regime transitions in modern Chinese history, had employed multiple genres of Japanese sources – photographers, translation works, journalist reports and so on – to enrich its content and reinforce its original mission, viz., to encourage Chinese women to have their voices heard and words read. Articles about Japan, both the country and the people, occupied a considerable portion of almost every issue. The paper attempts to shed light on Japan’s cultural influence on China when China started its long journey towards modernization. It argues that it was not any Western country that provided knowledge and insights to China, but rather Japan, the proxy of Western modernity in East Asia, that shaped the thinking of Chinese women. To recognize the Japanese role is important also because it helps to free East Asian history from the grip of politics.

Day 2

Special guest speaker: Hitoshi Kato (professor, Osaka University, Center for Japanese Language and Culture) Reconstruction of Buddhism in Modern Japan: Inoue Enryō’s Classification of Teachings (Kyōsō-hanjaku)

With the beginning of the Meiji era, Japanese institutional Buddhism suffered severely from the new government’s policy that distinguished between Shinto and Buddhism [Shinbutsubunrirei] and the movement to abolish Buddhism [Haibutsukishaku] that occurred with it. Furthermore, the spread of Christianity added to the weakening of Buddhism in Japan. Under these circumstances, a Buddhist thinker emerged, who, as a counter to Christianity, attempted to reconstruct Buddhism by interpretating it as a modern system of thought with reference to Western philosophy. This person was Inoue Enryō (1858–1919).

In order to clarify the characteristics of Inoue’s ideas and its problems, this presentation focuses on his Kyōsō-hanjaku or classification of teachings.

Kyōsō–hanjaku was a method that systemized Buddhist teachings by evaluating and classifying the order and content according to whether a teaching is superior or inferior. This was considered a fundamental characteristic of Buddhism in China, and had been variously practiced in Japan as well.

As Inoue himself had mentioned, though the traditional Kyōsō–hanjaku as annotation-study had been valid among Buddhist sects, a new Kyōsō–hanjaku based on philosophical thought was needed against Christianity.

To provide the pretext for this idea, it was necessary for Inoue to place Buddhism as a religion inherent to Japan. In order to do this, he adopted the evolutionary concept that Buddhism was a “living thing” that continuously evolved while adapting to the environments in India, China, and Japan. Inoue stated that this evolution would cause degeneration in terms of potentiality but would be seen as developmental in terms of existing power and that the existing Buddhism in Japan, which had undergone development, should, thus, be considered an authentic form of Buddhism. This was a radical change in thought because Buddhism had traditionally held a historical view [Mappō shisō] that it was at its most complete form during Buddha’s lifetime and would decay as time passed.

With reference to the dialectic development of philosophy in the order of materialism, idealism, and the synthesis of the two, i.e., “rationalism,” he insisted that there clearly existed a similar development in Buddhism, and divided the ‘School of Theory’ of Buddhism into three categories: ‘Sect of Being’ [‘Hīnayāna’], ‘Sect of Emptiness’ [‘Provisional Mahāyāna’] and ‘School of Middle Way’ [‘Proper Mahāyāna’]. The first category would include the Kusha and Jōjitsu sects, the second one the Hossō and Sanron sects, and the third one the Tendai, Kegon, and Shingon sects.

Though it was a matter of logic, a ranking of teachings was necessary when considering the development from the Kusha to the Shingon. However, Inoue believed that when starting with the Kusha, which took the position of dualism of matter and mind (busshin nigenron), and ending with the Shingon, which took the position of dualism, the teachings then circled back to the Kusha, at which point each teaching became equal. He stated that the difference between teachings of the Kusha and the Shingon was whether matter and mind were separated or non-obstructively interpenetrated. This was part of Inoue’s intention to reconstruct Buddhism as an intellectual system.

However, in Japanese Buddhism published in 1912 (seven years before his death), due to his further elaboration on the overall structure of Buddhism, such as dividing the ‘Sect of Theory’ into ‘Philosophical Section’ and ‘Religious Section’, ‘Philosophical Section’ into ‘Hīnayāna’ and ‘Mahāyāna,’ and then ‘Mahāyāna’ into ‘Provisional Mahāyāna’ and ‘Proper Mahāyāna,’ it instead highlighted discrepancies in the relationship between categorized divisions, causing the very system to collapse.

Pauline Rouleau (graduate student, Université Jean Moulin –Lyon 3) Miko: Mythological and Shamanistic origins

When visiting a Shinto sanctuary, one cannot but see miko. Miko, whose name is translated into English by “Shinto priestesses “, are well-known for helping clean the sanctuary, performing ceremonial dances, writing omikuji (written fortunes) and taking care of the sanctuary shop if any.

These are their modern functions. However, from ancient times to the Meiji Restoration, their role was quite different. They just performed ceremonial dances and also issued oracles. Even if nowadays miko still perform dances during matsuri (festivals), especially during miko kagura, they do not have the same role and the same impact on Japanese culture and Japanese people as they did before.

Few people in Japan know about their origins, which are more complex than they may seem. Miko are said to be the descendants of the goddess Ame no Uzume who danced in front of the cave where the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu ô mikami, had been hidding. This episode of Japanese mythology is recorded in both “Kojiki” and “Nihonshoki”, the imperial chronicles which were written in 712 and 720. On the other hand, miko’s behaviours during kagura, even nowadays, show that they also have shamanistic origins. Indeed, it has been proved scientifically that, since ancient times, there have been both male and female shamans in the Japanese archipelago who seem to have had a great influence on the functions of miko.

After talking about miko’s functions nowadays, I will analyse the myth of Amaterasu ô mikami hiding in the cave and the dance performed by Ame no Uzume. This dance, which is quite famous in Japanese mythology, can still be found in kagura during some matsuri. In this presentation I will first talk about the way this dance is performed in Takachiho Yokagura, and then compare it to the representations of the same dance in other kagura.

However, it seems that Ame no Uzume’s dance, which is said to be the first ritual in the history of Shinto, has been greatly influenced by shamanism. Indeed, as I said before, miko’s origins are to be found in shamanism as we can see by comparing different kagura and matsuri rituals. The present kagura and miko can thus be traced back to Japan ancient shamanism.

Radu Leca (doctoral candidate, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies) The Poet and Margareta: the Refraction of the Feminine Image of Japan within Romanian Culture

I analyse two Romanian embodiments of Japanese culture as the figure of the Japanese woman in traditional attire. The first are a series of poems on Japanese themes by the interwar poet Alexandru Macedonski. The feminine doll is a key element in Macedonski’s oriental fantasy. I argue, however, that this reveals more than just a mimetic local adaptation of Japonisme. This feminised image of Japan was as much an image of the Western myth of Japan as it was a product of Japan’s self-promotion as, paradoxically, a modern nation. For example, throughout the first decades of the twentieth century kimonoes were featured in exhibitions at the Mitsukoshi department store in Tokyo as examples of modern feminine dress. And interwar diplomatic exchange between Japan and the US included gifts of dolls from both sides.

Macedonski’s ‘Japanese doll’ was embodied by the pop singer Margareta Paslaru in 1969 during her participation at a music festival in Tokyo. During her stay in Tokyo, Margareta creatively appropriated the feminised image of Japan in a series of photos in which she was either dressed in traditional Japanese attire or posing with a similarly dressed doll of a Japanese woman made by Mitsukoshi. Margareta alternated this Japanized look with stage costumes that reworked motifs from Romanian traditional dress. I thus argue that Margareta, consciously or not, engaged with histories of performative self-representations of nationhood within both Romania and Japan.

Carmen Sapunaru Tamas (lecturer, Kwansei Gakuin University, School of Science and Technology) The After Midnight Pursuit of Happiness

There are a lot of stereotypes regarding Japanese society, and one that has persisted since times when the Japanese language was comprehensible only to a very limited number of people is the idea that it is impossible to know for sure what a Japanese person is thinking. They are polite, reserved, always acting according to a very strict set of rules and always hiding their true feelings behind a smile. The question my presentation will address is how we can explain the relationship between this stereotype and the more and more numerous images of salary men collapsed on stairs and sidewalks, sleeping peacefully on train and park benches, or simply taking a nap in the public house that contributed to their temporary state of bliss.

Last year before Christmas, posters advertising a concoction that would allow you to drink more without feeling sick were abundant on trains in the Kansai area. The protagonists of the advertisement? Mature men, company presidents who must celebrate the end of the year in style, young men, the model employees who can never say no to their bosses, and young women ready to paint the town red during a girls’ night. Cigarettes are bad, drugs are evil, even dancing hours are restricted in Japan, but alcohol is an acceptable part of daily life. People work because they must, and they drink because they must work. Alcohol is an ephemeral antidote to stress and loneliness, while bars and pubs are substitutes for relationships and home-like environments. My presentation is based on a case study and will attempt to analyze the mechanisms that support the day/ night contradictions in Japanese society, as well as the instinctive pursuit of happiness.

Peter Szalay (doctoral candidate, Osaka University, Graduate School of Language and Culture) Extraordinary Child-births in Japanese Folk-lore

In this paper I will discuss how the Japanese folk-lore interprets extraordinary child-births and children. There was a time when children who looked different or developed faster than the others were considered abominable in Japan. These children were called “demon-children” (onigo) and often got thrown away or killed by their parents, who feared that they would bring calamity on the whole family. I will pick up the stories that tell about a serpent as an unknown paramour visiting a woman by night, whose true identity will be found out by the means of a string and a needle attached to its garment by the woman. There are two different endings to this story. In one, a child will be born and become a local hero, in the other one the woman will have a miscarriage. There are areas in Japan where local tradition links the former tale with molar pregnancy, an abnormal form of pregnancy, in which the placenta villi converts into a mass of grapelike, translucent vesicles filled with watery fluid. Back, when medical science was not as advanced as today, Japanese thought that unusual events, such as extraordinary childbirths were the acts of superhuman. In the latter story, a child is born, but because of his chapped skin, slender body, etc., in other words, because he is different from the other children, he will be once again linked to the otherworld or the superhuman. However, there were mothers who chose to raise their children, ignoring the customs of the community. If such a child achieved great deeds once grown up, the community tended to explain that his abilities were due to his inherited blood from the superhuman being. Good or bad, the unusual has to be related to the superhuman in the Japanese folk-lore.

Oana Pavaloiu (graduate student, University of Bucharest, UNESCO Department) Between Biology and Culture. Cultural Perspectives over Maternity in Europe and Japan

Maternity has been thought for a long time to be a biological function women cannot escape or refuse as it is deeply rooted in their nature. However, nowadays we know that more than a biological function, motherhood has a social and cultural role which has been established from ancient times through a various range of myths. In this chapter we will analyse motherhood related myths and beliefs in European and Japanese culture trying to highlight both similarities and differences between these two cultural spaces.

In what concerns the cultural legacy over maternity perspectives, we will focus on the Greek and Japanese mythological legacies, by trying to prove that there are still various stereotypes and beliefs about women’s role in reproduction that were transmitted from ancient times to our societies. This analysis will help support one of the major objectives this paper, which is proving that maternity is a concept highly imbued with cultural beliefs, tributary especially to religion and culture, whereas not only to biology as it is generally thought. This is the reason why we chose these two different and distant cultural areas in treating this subject. On the one hand, the European perception over maternity was shaped in a great extent by the Greek myths and Christianity, layers on which local beliefs and superstitions overlapped. On the other hand, the Japanese perception is tributary both to the indigene Shinto beliefs and to the morals of Confucianism.

Adelina Vasile (“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University) Violent Encounters: The Search for Numinosity in 90’s Japanese Literature

As critics like Stephen Snyder, Philip Gabriel or Susan Napier have noted, there is, besides the constant urge to narrate the self, the desire and search for some form of transcendental spiritual experience in contemporary Japanese fiction.

The paper starts with an exploration of how the numinous experience has been defined, beginning with Rudolf Otto’s identification and elucidation of this ineffable experience in his The Idea of the Holy.

The paper focuses on the prevailing forms that the numinous takes in some novels published in Japan in the 90’s: Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1994-1995), Ryū Murakami’s Piercing (1994), Yōko Ogawa’s Hotel Iris (1996) and Natsuo Kirino’s Out (1997).

The major paradigm in which numinosity is located is the body in its sexual aspect and in relation to gruesomely violent action. The experiences probed by the writers are demonstrations of the dreadful, terrifying aspects of the numinosum; they embrace ultimate forms where felt pain, torture or even annihilation of the self or the other are central, ranging from violent eroticism to eroticized violence (violence that supplants sexuality).

The writers speak from the very heart of horror, creating diabolical scenes that are chilly and hard to stomach. Nevertheless, rather than being labeled as being merely evil and difficult to recuperate as art, such scenes should be understood and valued as being successful attempts at imagining the unimaginable, at describing experiences that tend to elude description and transcend simple binarities of good/evil, beauty/ugliness, meaningfulness/meaninglessness.

These fictional invocations of the numinous are hauntingly fascinating excursions into the dark netherworld of the human psyche and psychopathology, thought provoking attempts at piercing the thick veil enveloping the mysteries of eros and thanatos.

Monica Tamas (doctoral candidate, Osaka University, School of Graduate Studies) Silencing the Woman. Yōko Tawada’s Short Novel “The Bath”

Yōko Tawada was born in Tokyo, but has lived most of her adult life in Germany, writing in both her native tongue and the language of her adoptive country. Her poetics, constructed at the crossroads between languages, cultures and meanings, break familiar patterns and unravel worlds of strangeness, where words are tangible, bodies transform and souls travel unhindered.

Tawada’s second published book, “The Bath” (Japanese title Urokomochi), contains many of the motifs that the author has subsequently developed in her writings and is a text of major relevance in understanding the Tawada “matrix” of symbols and meanings. The main character, who is also the first person narrator, is a young Japanese woman living in Germany. She relates her repeated efforts and failures at fixing an identity created outside her. Her body becomes the place of negotiation between two patriarchal cultures: first, Germany, represented by her boyfriend Xander, who puts make-up on her face in order to make her look “more Japanese” and teaches her his language, hindering at the same time any form of self-expression, then Japan, depicted by a very muscular mother who offers her a mirror as a gift and several Japanese male chauvinist figures.

The narrator faints during a business meeting where she was interpreting and is rescued by the ghost of a woman whose face is half-burnt, a character inspired by the Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann and her novel Malina. The ghost steals the narrator’s tongue, leaving her speechless, but this muteness can be interpreted both as a way to defy patriarchy or the means to surrender to it, as we can read in feminist analyses of Freud’s hysterical patients suffering from aphasia. The maternal metaphor comes to balance the encounter with patriarchy and emphasis the possibility of rebirth and recreation.

Day 3

Irina Holca (assistant professor, Osaka University)

Showing and Showing off: Japan at the World Fairs

The first world’s fair, ambitiously named “The Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations”, was held in 1851 in London. Despite its name, the event featured mainly exhibits from Britain and its colonies (about half), followed by those from other imperial powers of the time, while Asia was represented meagerly, and in bulk. Japan made its first appearance at the Great London Exhibition in 1862, where objects from Alcock Rutherford’s private collection were displayed. The 1867 Paris Exposition had two “Japans” on show, as both the Satsuma clan and the bakufu scrambled to send to France representative exhibits. Later, at the 1904 Louisiana Expo, the Japanese pavilion took over the space assigned to Russia, too, after the latter’s delegation pulled out as a consequence of the ongoing war between the two countries. Fast forward to 1940: Tokyo was preparing to host the first Asian world’s fair, planning to integrate it with the celebrations of 2600 years since the enthronement of emperor Jinmu, the legendary first ruler of Japan.

Having come a long way in the one and a half centuries since their inception, the world’s fairs have been created to encourage peace and understanding, to educate the masses about new technologies and faraway lands, while also entertaining them. Sometimes held in tandem with the Olympic games, they also have offered one of the best chances for countries to “flex” their national “muscle”. In this presentation, I will look at the history of Japan’s participation in the international expositions, shedding light on the changes and continuities in her self-promoting discourse. My goal will be to link this analysis with the current state of affairs, and point out the problems inherent in the ambivalent self-image that Japan projects, domestically and internationally.

Erin Brightwell (associate professor, Hiroshima University) Triangulating Traditions: Cultural Synthesis in Japan’s Medieval Mirrors

Around 1008, Murasaki Shikibu produced an exchange between the brilliant Genji and his adopted daughter Tamakazura that contrasted Chinese-style historical “chronicles” and Japanese-style “tales”; in so doing, she put forth ideas that would come to shape discussions of Japanese writing about the past for over a millennium. Even today, when most dismiss such binaries as China-versus-Japan, Chinese-versus-Japanese, or fact-versus-fiction as reductive, the dualistic view put forth by Genji vis-a-vis accounts of the past has retained surprising sway. One result of this is that efforts to interrogate medieval histories and historiography in ways that fundamentally challenge these categories have been limited to date.

This paper proposes that Japan’s medieval kagamimono 鏡物 (Mirrors) constitute a powerful corrective to Genji-derived analyses of literary-historical texts of the period. Although the earlier Heian Mirrors—three vernacular historical tales about Japan—fit fairly neatly into a “foreign-versus-native” binary, I argue that an examination of the Kamakura Mirrors reveals a genre of writing that has changed to include linguistic, stylistic, and thematic innovation through creative reengagement with continental Chinese literary, historiographic, and intellectual traditions. Focusing in particular on the mid-thirteenth- century Kara kagami 唐鏡 (The Mirror of China), I analyze the ways in which its author negotiates with and refashions these traditions to present a new historiographic voice, one that defines itself not in terms of China-versus-Japan but as a masterful and selective synthesis of both. This enables The Mirror of China to afford a fresh perspective on the fluidity of medieval conceptions of language and genre, as well as the authority inherent in acts of narrating the past.

Angela Dragan (lecturer, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University) Santo Kyoden’s Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki

Santō Kyōden山東京伝 (1761-1816) is known today as a gesaku writer of the later 18th century. He was also active, however, as an ukiyo-e illustrator under the name of Kitao Masanobu北尾政演. The breakthrough in his career came in 1782, when Ôta Nanpo in his gesaku critique, Okame hachimoku, ranked Masanobu as an ukiyo-e artist in second place after Torii Kiyonaga. Nanpo also praised Kyōden’s kibyōshi, Gozonji no shōbaimono, which the author had illustrated under his artistic pseudonym, and cited both text and illustrations for their excellence. But it was Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki that brought him fame. Its main character, Enjirō who aspires to be an Edo playboy and its broad flat nose, botan no hana 牡丹の鼻, illustrated by Kitao Masanobu, became one of Kyōden’s trademarks.

We thus see that Santō Kyōden/Kitao Masanobu acted as a creator who reached high skill in two professions, both as an artist and as an author. Kibyōshi, known for their balanced blending of text and image, in many ways represented the best medium for Kyōden to express both of these skills.

I will discuss, in this presentation, two scenes from Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki and I will try to show the interaction between the verbal and visual elements. This is seen as a follow up of my previous presentation in this conference.

Maria Grajdian (associate professor, University of Nagasaki) The Return of the Feminine Woman or on What the Tale of Princess Kaguya (Ghibli Studio, 2013) and Frozen (Disney, 2013) Have in Common

This presentation takes into account the aesthetic-ideological dimensions of animation works within broader soft power endeavours on an international level via specific artistic strategies such as emotional ambivalence, the dynamic reconsideration of legends and myths, the subtle highlighting of the spiral-like dialectics of cause and effect. Its goal is to point out the intricate levels comprised by the phenomenon of the “feminine self” as media-related construction in the unstable stress-ratio between individual aspirations and historic-geographical embedding. Thus, it becomes obvious that beyond being a physical appearance with clearly defined standards of “inside” and “outside”, the “feminine self” is a highly personal concern, related both to the socio-cultural context of its emergence and to the economic-political path of its development. In times of the ubiquitous Cool Self symptomatology, the reinvigoration of local myths and legends provokes a nostalgic U-turn towards a more classical worldview with the simultaneous intellectualisation of popular culture encompassing the rather conservative message that love, happiness and existential fulfilment are more than ever individual choices in late-modernity.

Raluca Nicolae (associate professor, Technical University of Civil Engineering, Bucharest) Looking Taboos and the Masculine / Feminine Sense of Closure: Blue Beard and the Crane Wife

In the Motif Index of Folk Literature, Stith Thompson devoted a whole chapter to the taboos in various forms and on different continents. The Looking Taboo (C 300) centers on the episode of Orpheus and Eurydice, particularly on the Orpheus’ journey to the realm of the dead to bring back his beloved wife on the condition not to look at her. Since he breaks the taboo, their reunion fails and they are forced to live forever in different worlds. In Japanese mythology, the story of Izanami and Izanagi gives an accurate account of a similar plot: the goddess Izanami forbids Izanagi to look at her while she is still in Yomi no kuni (The Land of the Dead), but he cannot help peeking at his wife only to discover that she was a rotting body. In addition, the Japanese folktales provide a plurality of examples concerning the looking taboo such as Hebi Nyōbō [The Serpent Wife], Sakana Nyōbō [The Fish Wife], Hamaguri Nyōbō [The Clam Wife], Tsuru Nyōbō [The Crane Wife], in which the female character asks her human husband not to look at her while she is weaving / cooking / giving birth to a child. Each story ends with the parting scene of the couple, because the taboo imposed by the female character was broken and her true form is no longer a secret. Yet, in the Japanese folktales the breaking of the taboo is not perceived as a cosmic punishment with catastrophic outcomes. The story needs to be (sad and) beautiful, not necessarily moral, therefore the aesthetic element is the only life-sustaining constituent of the story. On the other hand, the tale of Blue Beard is a violent description of the severe consequences of violating the looking taboo. The wives of Blue Beard were asked not to peep at the forbidden chamber and they paid with their lives for breaking their husband’s prohibition and for subverting his authority. Either they are about a restriction imposed by a woman (as in The Crane Wife) or a taboo inflicted by a man (as in Blue Beard), the two stories are providing different perspectives on marriage: one underlining the aesthetic closure, rapport and the need for trust, the other emphasizing the authority and the centuries old feminine submission to the will of the husband.